I have been spending a lot of time lately trying to genuinely grok subtleties of Scrum and Kanban. The interesting things are those right in front of your face that seem so innocuous at first glance. Like the thing I noted on the train as I traveled by from Brussels to Amsterdam a few weeks ago. I had just left the Scrum.org face-to-face trainer?s meeting and was on my way to attend the new Professional Scrum Product Owner course. I was riding the train with Ken and Chris Schwaber, although we were in separate cars as we purchased our tickets at separate times. This turned out to be a good thing because it gave me time to just sit and reflect.

This is the thing I reflected upon:

What vs. How

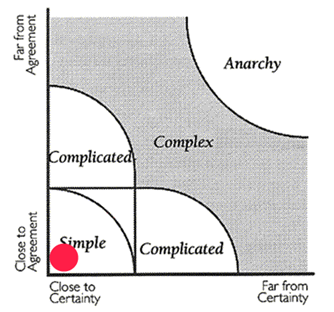

If we let one axis of Ralph Stacey?s certainty matrix be ?What We Will Make? and let the other axis be ?How We Will Make It?, we can observe interesting things. Scrum is optimized for complex work, in which there is a significant level of uncertainty in both What and How. Continuous flow systems, like Kanban, are well suited for complicated work, or even simple, in which at least one of ?What? or ?How? is known very clearly and the other is not terribly unclear.

Is Development Work Ever Simple?

Requirements can be well known, and so can technology. Were we to be certain of both at the same time, one might argue our position on the graph is as shown below:

Of course, we know that this is never really the case in the life. With software development the best we can likely hope for is complicated, because even changing a simple label on a page can lead to unintended consequences. In fact, even if a team is expert in tools and the language they will use to create a solution, there are other factors that lead to uncertainty on the How axis.

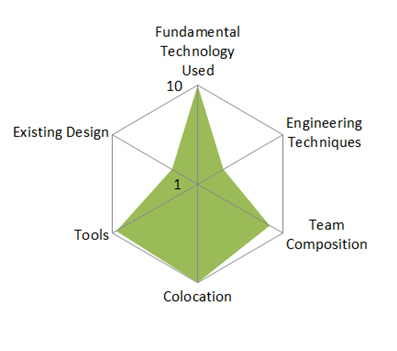

It may be appropriate to measure the Certainty of How by evaluating many context-specific variables. Below we see one way to quantify the Certainty of How by examining several factors we know are impactful to software development teams. There are many, many other variables that should factor into our analysis, and the variables will be context specific. For example, one team may choose to measure Familiarity with existing Framework as well as Ease of Changing Existing Code.? Another team might choose Pattern-based Development and Joe Won?t Take a Shower.

In the graph below, things we are certain about are a 10, those we are uncertain about are a 1 and the overall area represents % certainty of all variables.

What factors do you think significantly contribute to overall complexity in a team?

Of course, teams make investments in reaching higher levels of comfort and certainty with these things over time. For example, a team may understand it is immature with a technique it will be using on a project. If that is the case, they may choose to increase their level of familiarity with this technique over the course of the next Sprint. Once they do that, they are now more mature in this area. Maybe they can even get Joe to take that shower, thereby reducing friction on the team and the complexity of interpersonal discussions.

Now that we see the Complexity of How is a multi-variable derived value, I come to the basic question.

Can software development work ever be simple?

Even on very mature and hyper-performing teams there are many factors contributing to complexity, most of which we do not measure and monitor. There are so many variables we don?t typically bother to itemize them, and rather just swim through the Complexity of How. Scrum is designed to function well in the Complex zone of the Stacey Complexity Matrix, and continuous flow models are most effective in the Complicated or Simple zones.

The real truth is that when teams stay together and stay focused on the same product over time, they will get better at doing what they do. That is, the Certainty of How will increase over time.

That said, will it ever increase to the point that Scrum is no longer appropriate? Sure! This happens all the time and we see it in sustained engineering (maintenance teams) all the time. Complexity is usually low when all we do is support an existing application with bug fixes and minor enhancements. This is the home ground for Kanban. The only rub is that that the work is no longer terribly compelling and interesting for most developers.

Finally, wouldn?t it be great if Scrum ?did flex?to accommodate simpler work? More on that later ![]() .

.

“Scrum is optimized for complex work, in which there is a significant level of uncertainty in both What and How. Continuous flow systems, like Kanban, are well suited for complicated work, or even simple, in which at least one of “What” or “How” is known very clearly and the other is not terribly unclear. ”

Could you expand on that, because I don’t see how you’ve reached this conclusion.

I could answer: this is what is taught in the Professional Scrum Master course written by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland, or that this is what Ken asserts even after several hours of discussion (trust me:) ).

Instead I will note that this is evident with a second level of understanding of Scrum and why it works. Once you get beyond a mechanical understanding, this becomes clear.

This has been a core part of Scrum’s definition for 10 years.

That’s not really an explanation.

I think everyone I know who practices Kanban would disagree with it.

Oh! You took offense with only this line, then:

Continuous flow systems, like Kanban, are well suited for complicated work, or even simple, in which at least one of “What” or “How” is known very clearly and the other is not terribly unclear.

This is pretty easy to see. If we try to even out flow in a system, we must make items of processing similar sized. In order to do that, we must reduce the scope to contain complexity such that is not as complex. Bottom line is that smaller batches are simpler and that is a fundamental tenant of smoothing out flow.

Oh, I’m not offended. It’s only code ;).

It is not inherent in Kanban software development that the items of processing must be similarly sized, though I can imagine why that might be thought.

Thanks, I understand what you mean now.